Featured Stories, MIT, MIT EAPS, News | May 3, 2016

EAPS Dives into the Pale Blue Dot at the 2016 Cambridge Science Festival

By Lauren Hinkel

For MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS), every day is Earth Day. But on April 22nd, 2016, they were excited to share their knowledge and enthusiasm for it with the greater Boston community at the MIT Museum during the Cambridge Science Festival.

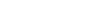

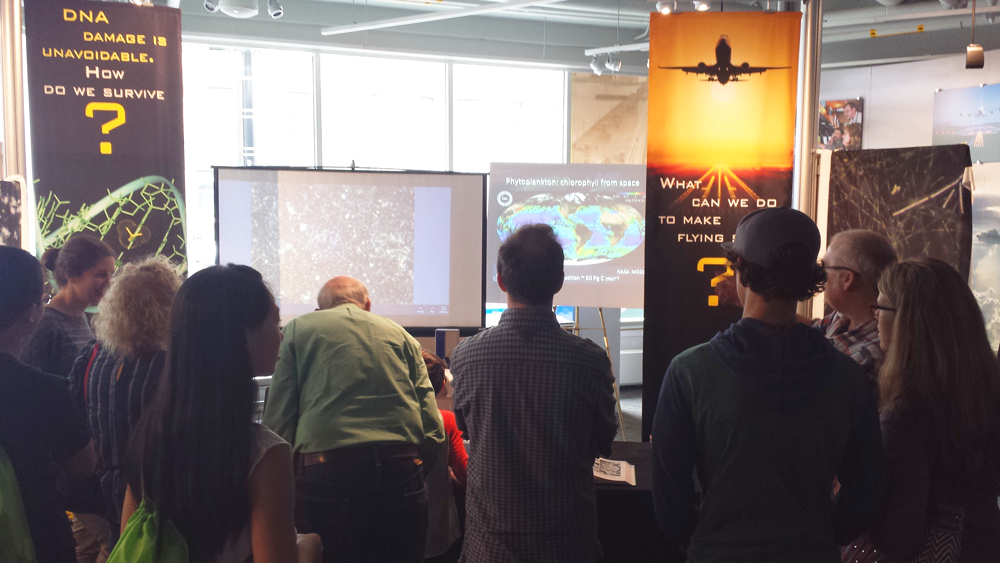

The annual Festival brings together scientists—ranging from young explorers and enthusiasts to communicators and researchers—for ten days of fun and accessible exhibits, lectures and interactive events. Professors, postdocs and graduate students from EAPS were pleased help the Cambridge Science Festival celebrate its 10-year anniversary by “Diving into the Pale Blue Dot”, exploring physical oceanography, marine organisms and climate with engaging displays and explanations informed by their own research.

Young families, couples and students made up the majority of the 457 visitors that day. Many were from the greater Boston area, but some traveled from as far as Chile and the Ukraine specifically to get a peek into MIT’s world.

Magnifying Marine Worlds

With the naked eye, water from the Charles River can look mucky and green, but Mick Follows, an associate professor in EAPS and leader of the MIT Darwin Project, knows to look closer. A compound light microscope zooms in on a petri dish with a fresh sample that postdocs David Talmy and Jon Lauderdale collected the day before, along with water from the harbor and Jamaica Pond for comparison. A projection of the magnified sample was shown on a large screen, next to it, a movie of global chlorophyll in the oceans. David Petrof, a young boy, moves in for a closer look.

He stares through the microscope. To David—who usually enjoys playing with his circuit board—the aquatic world seemed foreign, like small bugs swimming in a matrix of crystalline structures. Dinoflagellates, daphnia, phytoplankton and copecods are just some of the marine organisms that call these waters home. Posters and a book lay around the microscope table, helping visitors identify creatures as they flit through the screen.

David’s mother stood nearby watching. “It’s nice that you can just come down here and go to your local puddle and see what’s there. Experiences like this are great; it’s something tangible that both kids and adults can understand,” she said.

Dumping in the Seas

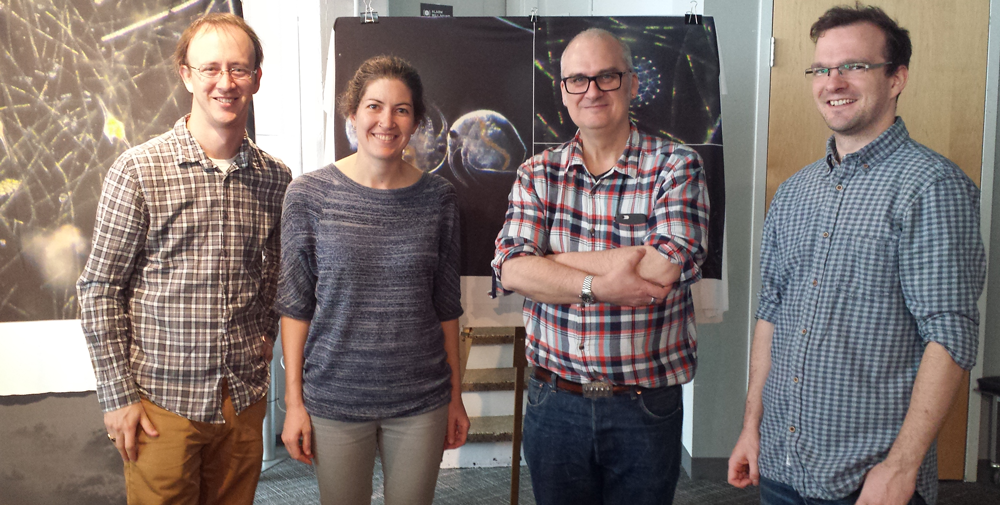

“Plastics get into the ocean and turtles eat them,” a boy of 6 years remarked while throwing paper dots into a water tank. Positioned on a turntable, the water tank modeled the physics of the Pacific Ocean and its currents. The dots began spiraling clockwise from the edge toward the center as the table spun. Fans blew on the water, mimicking air currents that help drive the North Pacific gyre. Eventually the dots, representing trash, got caught in the gyre, forming a cluster known as the Pacific Garbage Patch, in the real ocean.

MIT oceanographer John Marshall and EAPS researchers and postdocs navigated crowds of visitors through the exhibit and explained how each physical process in the Pacific Ocean worked to concentrate debris into the gyre. The researchers directed attentions to overhead projections of the water tank as well as a slideshow, helping visitors to understand the mechanics at work and see how a piece of garbage on the land can find it’s way to the sea.

Many visitors knew that trash and plastics often ended up in the ocean, but most were surprised and fascinated by how they congregated in select ocean regions. Naturally, they inquired further. “So what happens to the plastic and what are we doing about it?” was a common refrain that the EAPS researchers fielded throughout the day.

“We don’t know enough about what plastics are doing in the ocean,” said Tracy Mincer, an Earth Day attendee and marine chemist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). With him were his wife, son and daughter. “There are some 25,000 metric tons dumped into the ocean globally,” he continued, “but we can’t account for [a large portion of] it.” Part of Mincer’s work is to understand where the plastics end up in the ocean ecosystem. “Not all of it is in fish; we’re finding it in ocean sediment studies. So, we’re looking to research this further.”

Several MIT researchers and students have joint appointments with WHOI and are currently looking into this and related matters.

Visualizing the Earth

We live in a data-rich world, and sorting out that information in a meaningful way can seem like an overwhelming process. But with technology at our fingertips, scientists can use visualization methods to help make sense of it.

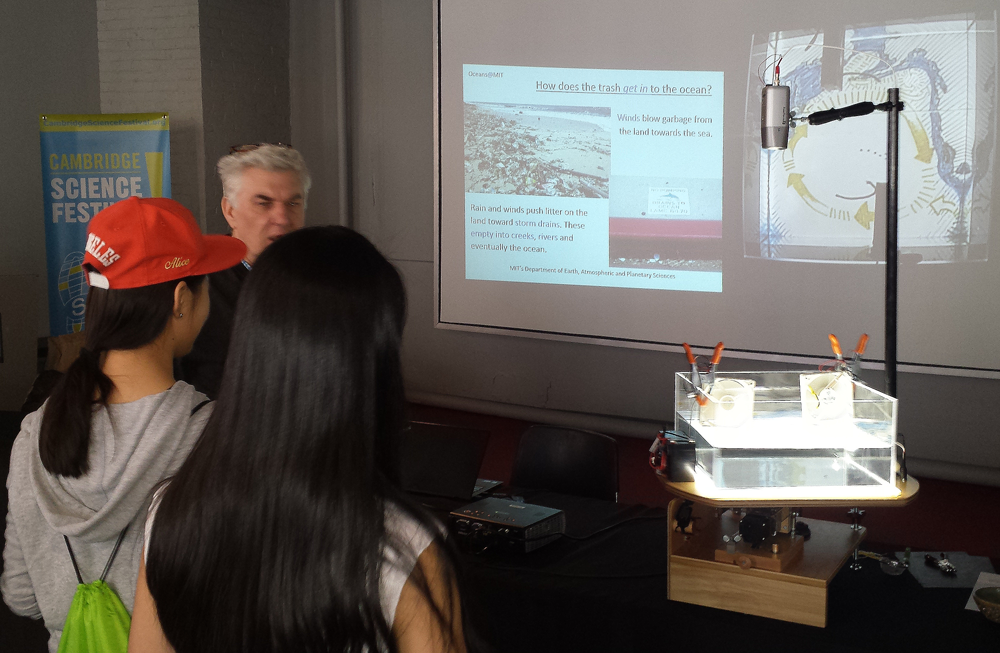

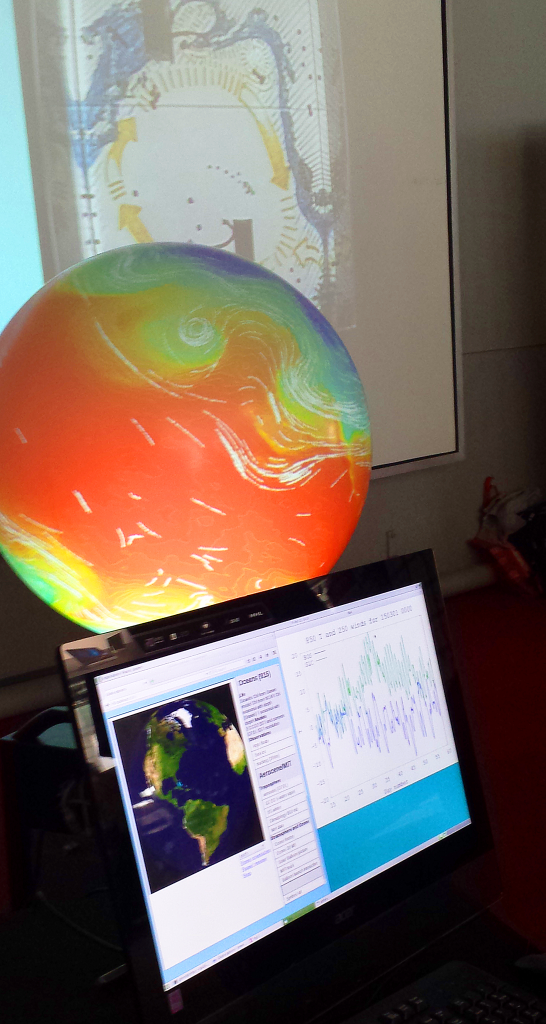

Enter the iGlobe, a large, computerized sphere that projects beautiful and mesmerizing displays of weather, temperature, ocean currents and more occurring around the world. It uses over 250 movies, incorporating real-time data, to illustrate historical Earth processes and future projections for climate change, atmospheric and oceanic changes and storms. Controlled by a laptop, viewers can metaphorically keep their finger on the pulse of the Earth, and explore how the Earth using various metrics, as looking down on the world from space.

The iGlobe/MIT project is funded by the National Science Foundation and presents a graphics-rich, customizable tool for climate education and outreach.

Visitors huddled around the globe as MIT oceanographer and iGlobe consultant Glenn Flierl adjusted the displays. Jean-Pierre De-La Cruz de Juesus and his father Sal shuffled from the Pacific Garbage Patch display over to the iGlobe. Flierl initiated the ocean currents display, and the eyes of the inquisitive pair lit up. They could see how local pollution could become the world’s problem, like the Pacific Garbage Patch. This prompted questions about what the plastics can do to fish, conversations about how plastics break down, what chemicals can leach out and concerns for other international communities.

With its displays, the iGlobe exhibit refocused visitors’ thinking from the microplastics seen in the garbage patch and the microorganisms in the water samples to broader environmental and planetary concerns about climate and pollution. They were able to step back and see the Earth’s interconnectivity and natural flow. Overall, guests of Earth Day event came away with an increased awareness and understanding of marine issues and research, as well as a curiosity to learn more.

***

This was Oceans at MIT’s fourth time participating in the Cambridge Science Festival. There were 457 visitors in attendance for the Earth Day event at the MIT Museum; about 65% of them were students. Events like these help make science fun and assessable to the public, as well as help develop the next generation of scientists and educators.

Oceans at MIT is dedicated to reporting on MIT and WHOI’s efforts to understand, protect, and harness the world’s oceans. Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter and stay up to date with our latest stories.

Participation was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant from Frontiers in Earth System Dynamics (FESD).