Featured Stories | August 19, 2015

The Hart of MIT’s Maritime Legacy

By Cassie Martin

The MIT Museum is a veritable treasure trove of scientific innovation and discovery. With exhibits ranging from robots and photography to ship models and ocean engineering, there’s never a shortage of interesting artifacts to be found. But what visitors spy in the gallery is only a small percentage of the museum’s intellectual wealth.

Behind the scenes, stacks of old wooden bookshelves and file cabinets house hundreds of thousands of relics documenting MIT’s maritime legacy. Kurt Hasselbalch, curator of the museum’s extensive Hart Nautical Collection, is bringing some of those artifacts to life in a new interactive online exhibit that will focus on the life and career of MIT alum Nathaniel Greene Herreshoff, widely considered the most influential boat designer in modern history.

“Herreshoff is quite symbolic of MIT’s excellence and overall contributions to ocean technology,” said Hasselbalch. “He’s the embodiment of what MIT’s founders had in mind—to train people who are affecting big change in the world by contributing to technology and science on a global scale.”

Before enrolling at MIT in 1866, Herreshoff was already a skilled boat designer. As a teenager, he helped his older brother John, who was blind, design wooden sailboats and yachts. But he was more interested in steam engines, which revolutionized global trade and communications. After graduating from MIT with an engineering degree in 1870, Herreshoff went to work for Corliss Steam Engine Company in Providence, Rhode Island, but continued designing for his brother’s company, Herreshoff Manufacturing.

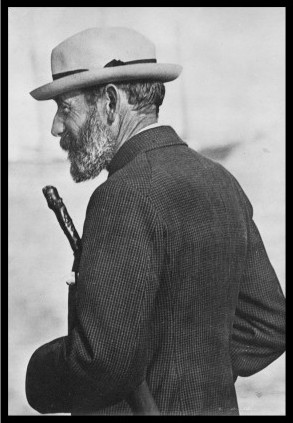

Together the Herreshoff brothers designed and built America’s first steam-powered fishing vessel in 1872, and Nathaniel joined the company soon after. During his tenure, the younger Herreshoff proved himself a maritime maverick. His notable accomplishments include designing six America’s Cup winning yachts in a row—many of which are still winning races today—introducing the world to modern catamarans, designing highly efficient steam engines and the very first ocean-going torpedo boat for the U.S. Navy.

Over the years, MIT Museum has acquired 14,000 original plans for more than 2,600 Herreshoff vessels in addition to thousands of photographs, original artwork, world-class models, and other technical documents. Each day, Hasselbalch fields hundreds of requests for copies of Herreshoff’s plans from around the world. Most people use the plans to update the approximately 400 existing boats, build models and full-scale replicas, and write historical articles, but Hasselbalch hopes to expand access and interest in the collection beyond this small niche.

Instead of keeping Herreshoff’s legacy tucked away, Hasselbalch and other museum curators are working to preserve these artifacts in a 21st century format while simultaneously making them widely accessible. Plans for the upcoming permanent Herreshoff exhibit will not only include an ultimate online archive, but also an interactive physical gallery. Visitors can expect to see rare original plans for America’s Cup winning vessels and other revolutionary designs such as Stiletto—a torpedo-type boat built in 1855—as well as experience what being on board these boats was like firsthand thanks to virtual models displayed on a media wall, among other things.

“We may also do some 3D printing, or manufacture a Herreshoff engine in the Edgerton lab,” said Hasslebalch. “We will have some original steam engines and maybe a small boat that Herreshoff built, as well as models of all his designs.” Other interactive elements will relate to principles of sailing, marine engineering, and hydrodynamics, so the public can understand the reality of designing in a fluid environment.

“We’re now in this era of exploding digital humanities, but there aren’t a lot of these maritime digital collections currently out there,” he said. “MIT has the possibility of leading the way in creating a world class archive for a world class maritime collection.” Hasselbalch and colleagues are currently fundraising to build the exhibit, which will likely debut in 2017.