Featured Stories | May 21, 2014

A Visit from the “Dragon” of Rapid Ice Sheet Collapse

By Genevieve Wanucha

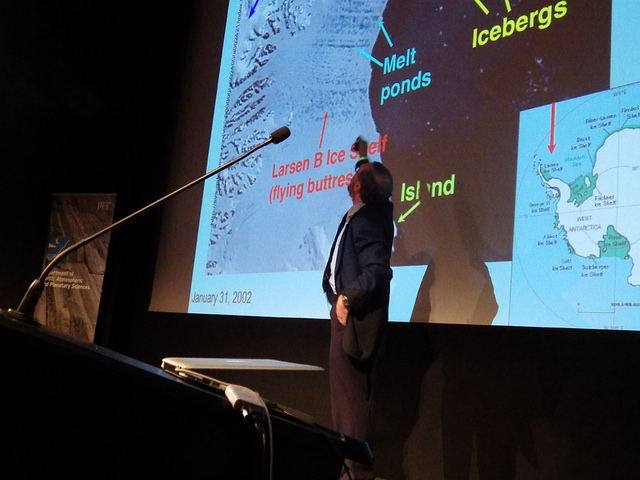

Just days after news broke that the West Antarctica ice sheet is headed toward rapid melting in the coming centuries, polar ice expert Richard Alley visited MIT to deliver the 14th Annual Henry W. Kendall Memorial Lecture “Ice Sheets and Sea Level: Is the Long Tail Attached to a Dragon?” The well-timed lecture delved into the process of ice sheet melting and addressed how to grapple with the risks and uncertainties of climate change and sea level rise.

Richard Alley, the Evan Pugh Professor of Geosciences in Penn State’s College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, is credited with showing that the Earth has experienced abrupt climate shifts in the past and will again, based on meticulous measurements in Greenland and Antarctica. He has spent his entire career trying to determine the likelihood of collapse of the West Antarctica ice sheet, which was first predicted by John Mercer in 1978. Yet, he and his colleagues have struggled to “cut the tail off” that “dragon” of a possible climate disaster in West Antarctica.

There is now evidence from multiple research groups that West Antarctica faces irreversible melting, which would eventually dump hundreds of trillions of tons of melted water into the ocean, driving up sea level to the high end of what we are actually planning for based on current IPCC estimates–10 feet or more in the coming centuries.

West Antarctica is melting because relatively warm water that occurs naturally in the deep ocean is being pulled to the surface by a strengthening, over the past several decades, of the powerful winds that whip around Antarctica. The wind intensification, Alley says, is probably due to a combination of natural variability in winds, atmospheric and warming due to human-driven rise of greenhouse gases, and the influence of the ozone hole.

Alley shared his most current insight into the process of ice sheet melting: ‘flexure.’ Ice shelves, which extend from an ice sheet and float over the ocean, rise up and flump down with the tide. The undulations of ice shelves suck in water into the underside of the ice sheet. If that water is warm, the exposed ice sheet thins and retreats at a faster and faster rate.

In the case of Antarctica, Alley says that melting will follow a “slowly, slowly, slowly, boom” trajectory. A century of slow melting of the shelves can eventually destabilize the entire ice sheet from underneath, triggering a chain reaction toward rapid collapse. This “fast after slowly” phenomenon seems to be a fundamental characteristic of melting ice sheets. In fact, Alley showed images of the particular patterns of ripples in marine sediment formed during rapid ice sheet retreats in the ancient past.

A skilled public communicator, Alley was able to put the risk of abrupt climate change into the context of our everyday lives with a humorous analogy. Because a serious traffic accident is such a big deal, we pour a lot of resources into traffic safety, even though a fatal accident is not the most likely scenario every time we get into a car. Alley made the argument that we, as a community, should treat the risk of moderate or extreme sea level rise in the same way. Specifically, he suggested the adoption of energy policies that take at least the IPCC projections for warming and sea level into account, such as a tax or fee on carbon.

Alley ended on an optimistic note, expressing that humans have the power to prevent other ice masses from rapid melting. “We are the first generation of humanity who can build a sustainable energy system that won’t change the climate much,” he said. “We know, for the first time, how to still have a world with ice sheets.”

The 14th Annual Henry W. Kendall Memorial Lecture was sponsored by the MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and the MIT Center for Global Change Science. The lecture series honors the memory of Professor Henry Kendall (1926-1999), a 1990 Nobel Laureate, a longtime member of MIT’s physics faculty, and an ardent environmentalist. A founding member and chair of the Union of Concerned Scientists, he played a leading role in organizing scientific community statements on global problems, including the World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity in 1992 and the Call for Action at the Kyoto Climate Summit in 1997.