Featured Stories, MIT, MIT EAPS, News | August 14, 2017

New Study Details Ocean’s Role in Fourth-Largest Mass Extinction

Global oceanic dead zones persisted for 50,000 years after end-Triassic extinction event

By Madeleine Jepsen | AGU Geospace

Extremely low oxygen levels in Earth’s oceans could be responsible for extending the effects of a mass extinction that wiped out millions of species on Earth around 200 million years ago, according to a new study.

By measuring trace levels of uranium in oceanic limestone that correspond to oxygen levels in seawater present during the rock’s formation, the new study finds areas of the seafloor without oxygen increased by a factor of 100 during the end-Triassic extinction event.

It took about 50,000 years for ocean oxygen levels to return to what they were before the extinction event and it may have taken as long as 250,000 years for coral reefs around the globe to fully recover, according to the study.

The new results shed light on the state of the oceans during the end-Triassic extinction, which wiped out approximately 76 percent of all marine and terrestrial species. The end-Triassic is the fourth-largest extinction episode in Earth’s history and occurred just before dinosaurs became Earth’s dominant land animal.

Scientists are not sure what initiated the extinction event, but suspect a burst of volcanic activity around 200 million years ago increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. That would have made oceans more acidic and caused ocean water to become anoxic. Severe anoxia causes “dead zones” in the water where low levels of oxygen cause marine life to suffocate and die.

Anoxia has long been suspected to have played a role in the end-Triassic extinction, but the anoxia’s duration and severity were not known, according to the study’s authors. The new study, published in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, quantifies the timing and extent of marine anoxia during and after the end-Triassic extinction, said Adam Jost, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT’s Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences department in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and lead author of the new study.

The large-scale anoxia that likely occurred during the end-Triassic extinction would have rendered many areas unable to sustain life, according to the new study. The persistent anoxia, or lack of oxygen, observed in the new study would have delayed organisms that survived the mass extinction from returning to low-oxygen areas and repopulating them.

Understanding the role of anoxia in the extinction event may be important, since the end-Triassic extinction can serve as a case study for biological adaptation to environmental change.

Determining past ocean conditions

Since uranium is well-mixed throughout the ocean, it can be used to examine global levels of anoxia, giving scientists information about the average levels of oceanic oxygen. Other methods can only inform researchers about local oxygen conditions, Jost said.

“It’s very hard to take those pieces of evidence and extrapolate what’s happening at a global scale,” he said. “[The ocean] could be anoxic [in one location], but if you go 100 kilometers away, it might not be anoxic at all. The nice thing about uranium isotopes is that along with the model that we construct, we can begin to quantify that change in anoxia, and determine how much area of anoxic ocean floor is required to generate the trends that we see in the uranium isotopes.”

Scientists can determine how much oxygen is present in ocean water by measuring the ratio of two forms of uranium in oceanic limestone: uranium-238 and uranium-235.

Oceanic limestone forms through the buildup of calcium carbonate from coral reefs and the shells of bivalves. Uranium that is also present in the seawater is incorporated into the calcium carbonate and eventually the limestone.

When seawater is anoxic, certain chemical reactions preferentially use the heavier uranium-238 over the lighter uranium-235. More of the uranium-238 becomes insoluble in ocean water, and can no longer be incorporated into calcium carbonate. Instead, the uranium-235 remaining in the seawater is incorporated into the calcium carbonate – and eventually the limestone – at higher levels than the uranium-238.

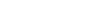

To study the severity of the anoxia during and after the end-Triassic extinction, researchers collected samples of limestone from the Lombardy Basin in northern Italy that were deposited during and after the end-Triassic extinction about 201 million years ago. They measured uranium levels in the samples, and found there was more uranium-235 than uranium-238 in the limestone, indicating there were anoxic conditions when the rock was formed.

Based on their measurements, the researchers estimated the timeframe for anoxia during the extinction. The researchers found ocean water was anoxic for at least 50,000 years during the extinction but delayed reef recovery for up to 250,000 years after the extinction event. Although there are other processes that could potentially cause uranium-238 or uranium-235 buildup in the sediment, the researchers used modeling to demonstrate these processes could not produce the elevated levels of uranium-235 they observed in their samples.

The study’s authors suspect the anoxia is what delayed the recovery of marine species during the end-Triassic and could have contributed to the extinction’s severity.

Jost said their conclusions about end-Triassic anoxia fit into a larger picture emerging from recent research showing many similarities between the end-Triassic extinction and the most severe extinction on record, the end-Permian, which occurred about 52 million years before the end-Triassic extinction. Understanding these extinctions can help scientists better understand how species may react to future changes in the environment.

“The end-Permian was much longer, and the recovery was much longer and the extinction more severe,” Jost said. “So in some ways, the end-Triassic is a mini end-Permian.”

Exploring Ancient Ocean Acidification in the Rock Record

Exploring Ancient Ocean Acidification in the Rock Record